Research Interests

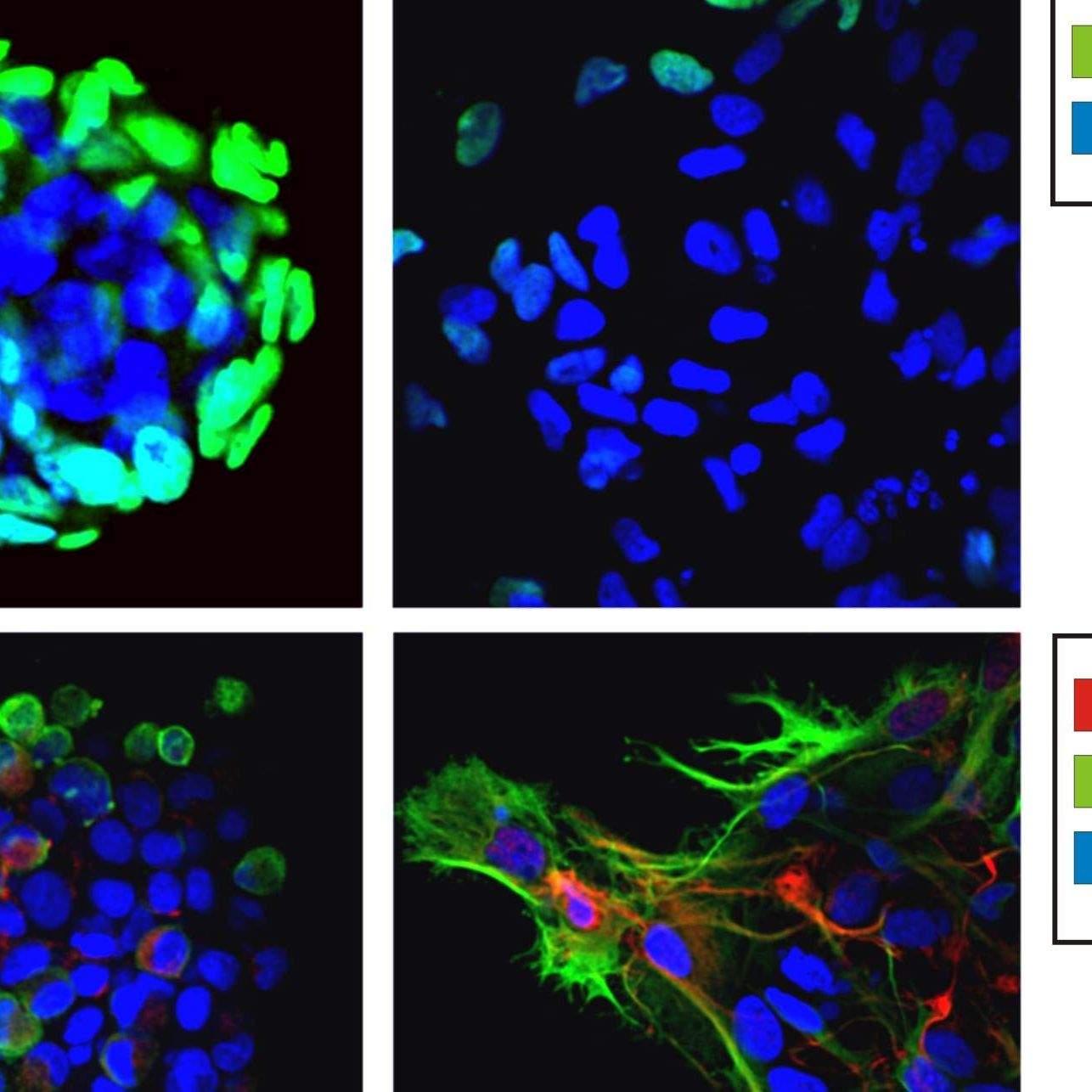

Stefano Forte’s lab is focused on the study of mechanisms and the identification of models of cancer diseases. Dr. Forte Laboratory Team has recently identified an in vitro model, based con tumor initiating cells, which is able to predict the efficacy of radiotherapy in vivo. The research group is also involved in developing in vitro oncological models based on patient derived tumor organoids (PDTO) and in the characterization of signaling events, mediated by extracellular vesicles, involved in tumor progression. Cellular and molecular substrates of these phenomena are what we investigate day by day.

Experimental Oncology

Every tumor responds to treatment differently. Although many studies have been conducted to identify the prerequisites for sensitivity to radiation therapy, the topic is still poorly understood. Locally advanced rectal cancers (LARC) are often treated with neo-adjuvant radio/chemotherapy for downstaging. Some of these tumors respond very well thus making subsequent surgery safer and increasing the remission rate. Some tumors respond so well that they undergo complete regression: if these cases were predictable, curative surgery would not even be necessary. On other occasions, however, some tumors do not respond to neo-adjuvant therapy. Being able to predict the response to radio/chemotherapy in advance would allow us to identify the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for each patient. It is also important to remember that radiotherapy, using ionizing radiation, can also produce toxic effects on healthy tissues. The toxic effects are directly proportional to the doses used. It would be useful to be able to predict the minimum effective dose to treat each patient. This would allow to minimize the toxic effects while maintaining an efficacy of the treatment.

In our laboratory we have developed an in vitro model which, in the cases analyzed, was able to predict the effect of in vitro therapy. We have studied this phenomenon in rectal and lung cancers. We isolated cancer stem cells from biopsies of cancer patients and treated the cells in vitro to observe their degree of response. We found that when cells responded to therapy, donor patients also had a better prognosis. In lung cancers, we were able to identify the lowest effective dose to kill cancer cells in vitro. This minimum effective dose is the same that can trigger a significant reduction in tumor mass in vivo.

In our laboratory we have developed an in vitro model which, in the cases analyzed, was able to predict the effect of in vitro therapy. We have studied this phenomenon in rectal and lung cancers. We isolated cancer stem cells from biopsies of cancer patients and treated the cells in vitro to observe their degree of response. We found that when cells responded to therapy, donor patients also had a better prognosis. In lung cancers, we were able to identify the lowest effective dose to kill cancer cells in vitro. This minimum effective dose is the same that can trigger a significant reduction in tumor mass in vivo.